The Artist who Influenced WWII Military Aircraft Pin-Up Nose Art

How a Peruvian illustrator rose to influenced US Military pilots and crewmen to fly their aircraft into battle with femme fatale nose art.

In the late 30s there were numerous illustrators and photographers who worked at Esquire, an American magazine that included photos and drawings of well-turned female bodies creating the new ideal of women through its central pages and photographs; However, the most prominent of the moment was George Petty, who popularized his Petty Girls.

The girls represented by Petty used to be accompanied by some comic phrase or aimed at capturing the reader's attention. Little by little, these girls were increasingly successful and the space reserved for these illustrations was increasing, while eliminating any element of distraction and the girls became the complete center of attention on a white background, where their physique and expression carried all the weight.

However, the great popularity

achieved by Petty's illustrations led him to increase his economic demands more

and more to the magazine. This led Esquire executives to look for a replacement

in 1940 that was at the level of Petty's illustrations, but charged less. The

substitute chosen would be the Peruvian artist Alberto Vargas. Vargas was born

in Arequipa in 1896 as the son of a renowned photographer, which allowed him to

grow between images, cameras and the artistic environment of photography and

learn how to use the airbrush. Soon he showed interest in drawing and would

march in 1911 with his family to Europe, where he would train as an artist in

Paris and Zurich, while increasing his interest in classical painting and especially

that of Ingres.

However, the great popularity

achieved by Petty's illustrations led him to increase his economic demands more

and more to the magazine. This led Esquire executives to look for a replacement

in 1940 that was at the level of Petty's illustrations, but charged less. The

substitute chosen would be the Peruvian artist Alberto Vargas. Vargas was born

in Arequipa in 1896 as the son of a renowned photographer, which allowed him to

grow between images, cameras and the artistic environment of photography and

learn how to use the airbrush. Soon he showed interest in drawing and would

march in 1911 with his family to Europe, where he would train as an artist in

Paris and Zurich, while increasing his interest in classical painting and especially

that of Ingres.

Later in 1916 he would move to

New York where he began his artistic career painting theater actresses with a

unique combination of elegance and femmes fatale. In this way Vargas created

the image of a social, sensual and elegant woman, who would become the new

goddess of the twentieth century, being the representation of the sophisticated

and independent woman of the country. In this way,

Vargas would work during the 1930s for numerous Hollywood companies making

portraits and movie posters, until in 1940 he was hired by Esquire to take up

Petty.

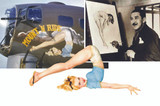

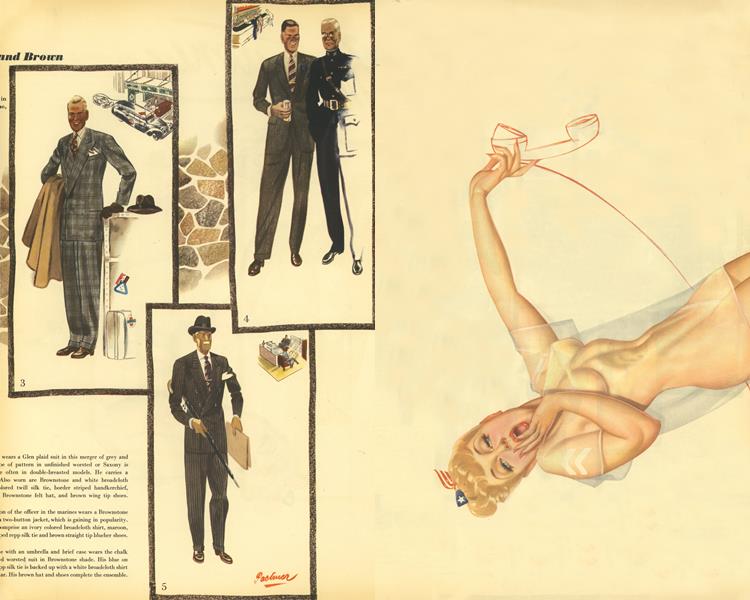

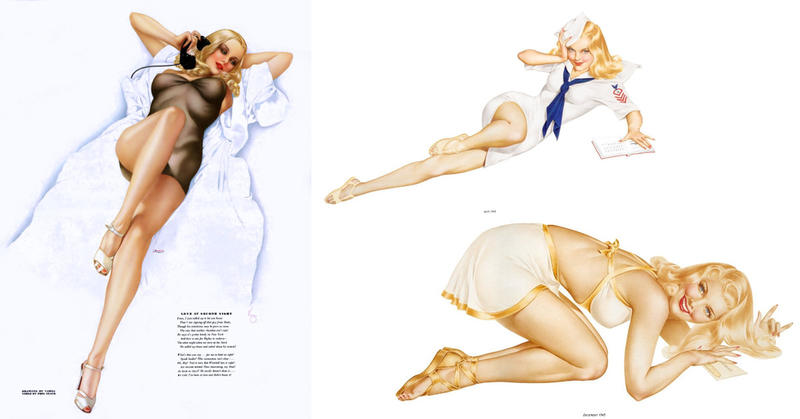

(Above) Pages from a 1941 Esquire Magazine

Vargas' first drawings appeared in October 1940, in which the pressure is perceived to maintain the previous style of his predecessor; however Vargas would soon impose his own style. His great acceptance by the public led Esquire to publish in December 1940 the first Vargas calendar, in which a girl was represented in each month, which had great commercial success. Vargas girls quickly became synonymous with the feminine sensuality, elegance and beauty of American women. In addition to the female audience, Vargas women represented a more credible female beauty model than the previous representations.

Vargas's great acceptance by the public led Esquire to publish in December 1940 the first Vargas calendar, in which a girl was represented in each month, which had great commercial success.

With the entry of the United

States into World War II in December 1941, women would return to occupy a

prominent role in society and changes would begin to occur in terms of women's

sexuality, with Vargas girls being a reference icon for women. New ideals of

women. Also with the outbreak of war, Vargas turned his girls not only into an

icon of female beauty, but also a patriotic icon of the American woman. Thus,

between 1942 and 1945 his drawings frequently referred to war, included

military elements or represented women belonging to some branch of the armed

forces (also offering the female audience a glamorous image that favored entry

into these units).

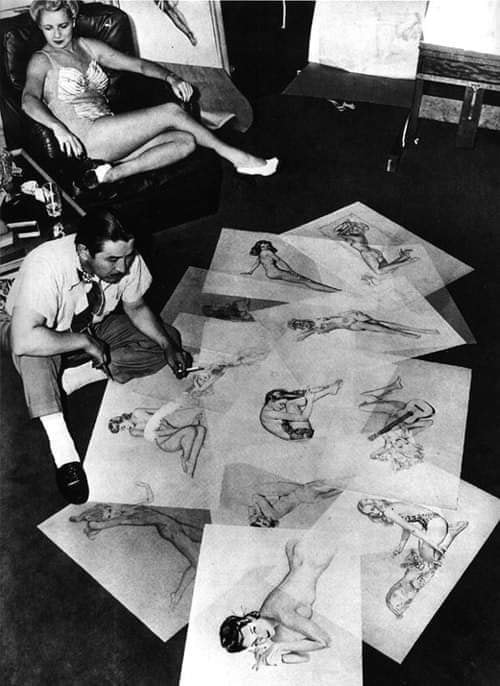

(Above) Vargas in Studio pondering over his work with a model lounging in the background.

It is noteworthy of the great

popularity that Vargas's work had among soldiers who were fighting abroad, who

quickly felt a strong bond with the woman he presented to them (since they

became a bond that united them with their homes , in the model and promise of a

woman that everyone expected to find on their return and in the only female

company they had with them in the harsh conditions of combat).  Quickly these

girls shared space in the lockers, barracks, trenches and even

vehicles with photographs of friends, family and President Roosevelt. Such was

the demand on the part of the soldiers, that between 1942 and 1946 the Esquire

magazine made more than nine million copies (without ads and free for the

troops), which were sent worldwide and distributed by the bases soldiers in

which the troops were stationed, to raise morale. In addition, along with the

magazine the calendars were widely disseminated, Esquire coming to include a

greater number of girls for their military editions.

Quickly these

girls shared space in the lockers, barracks, trenches and even

vehicles with photographs of friends, family and President Roosevelt. Such was

the demand on the part of the soldiers, that between 1942 and 1946 the Esquire

magazine made more than nine million copies (without ads and free for the

troops), which were sent worldwide and distributed by the bases soldiers in

which the troops were stationed, to raise morale. In addition, along with the

magazine the calendars were widely disseminated, Esquire coming to include a

greater number of girls for their military editions.

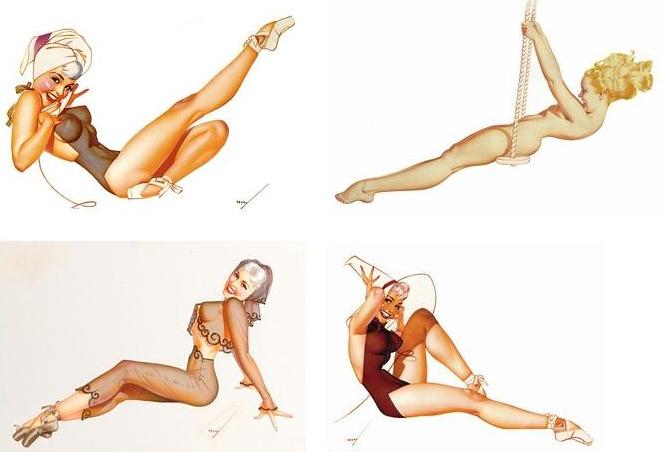

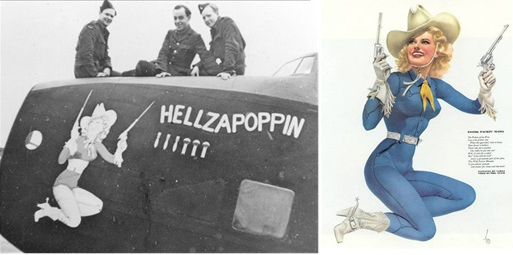

(Above) Hellzapoppin featuring Varga's "Two Guns" Pinup Artwork

Such was the influence of these works that were appropriated by the troops, which incorporated them into the fuselages of their planes in what is known as nose art.

(Above) P-38 "Dot Dash" with the popular pinup artwork inspired by Vargas.

The custom of representing the Vargas girls about the bombers quickly became popular, as they became a protective talisman for their crews, which reminded them of their home and why they fought. Inspired by the works of Vargas (although varying the level of nudity of the girls and often with a very provocative and aggressive sexuality) the soldiers painted them on their planes as a symbol of good luck or as a kind of goddess of war (at style of the bow masks used by the ancients in their boats), they also had their practical utility by serving as an element of distraction for enemy pilots during air combat.

(Above) An Airman touches up the artwork B-29 "Little Gem"

(Above) B-29 "Lady be Good.

At the end of the war the men returned home and recovered their jobs, so many women had to return to their traditional place in the home, so the woman saw cut part of the freedoms she had gained during the conflict to return To assume their traditional role. In this way after the war there will be a great boom in marriage and birth, which will lead to an ideal American woman based on a happy and dependent housewife (although the vision of the object woman characterized by her naive will also be maintained , but open sexuality). Marriage and motherhood became the best seen in a context of social repression that tried to leave behind the liberal behaviors of war. In this way, sex soon became a myth nourished by the media. It is not surprising, then, that in this very conservative context such images were left so ragged, that they brought a breath of fresh air.

About the Author/Contributor - Lewis M. Barrera

Lewis is WWII history enthusiasts and passionate about artist who made work in the early to mid 1900's. He lives in Punta Mita, Mexico

Are you a writer passionate about WWII art? We're looking for contributors! Contact nicj@aircorpsaviation.com for more info.